WATCHLIST: The Distinctive, Uninhibited Horror Films of Juraj Herz

After a year of figuring out this newsletter thing, I’ve spent a spell looking back and thinking about where I’d like it to go. I created Dead of Night primarily as a place to explore “the edges and possibilities” of the horror genre—and this is what I’ve been doing in the essays published here.

These essays will continue, though their form and subject-matter may evolve. The thing that got me hooked to the newsletters I myself read (more food and politics so far for me, less cinema), and that inspired me to write Dead of Night, was their devotion to the thoughtful, in-depth writing on a topic that I’ve tried to emulate in this space.

But this isn’t the only thing that newsletters do well. It’s an unusual format, read in multiple contexts—sometimes directly in the inbox, sometimes in a web browser, sometimes in a dedicated reading app. I typically take in a newsletter in two passes, first on my phone when it arrives, usually reading the more informal sections (recommendations, recipes, links), then reading the more in-depth stuff later in Instapaper on my tablet or on a web browser.

I’ve been thinking then about whether there’s anything more informal, more practical I could bring within the scope of this project (beyond the quite short “Horror Writing Elsewhere” feature I’ve been including at the end of each newsletter). And the idea I like is basically a way of “showing my work” with respect to the essays.

Like most obsessed cinephiles, and especially now with the newsletter going, I screen a lot of movies. And I do a lot of thinking about movies. Most of this watching and thinking never makes it into a piece of writing—or only does so indirectly or minimally.

This new feature (“Watchlist” I’m calling it) is meant to provide a useful guide to the horror films I’m watching (some of which will of course pop up again in the essays). It’s a chance to take a quick look at a body of work, a subgenre, or films with some thematic connection. I’ll try to highlight interesting threads and cul-de-sacs, and to pick out the most notable, fascinating films I come across. I’d like “Watchlist” to be a quick read that opens up an area of horror and points a reader in an interesting direction.

Here it is then—the first “Watchlist.” A look at the horror features of fascinating weirdo Juraj Herz.

While he worked across genres, Czechoslovakia-born, Prague-based director Juraj Herz’s signature genre was horror, though none of his horror films (save for maybe one, Darkness) would be described simply as horror films. They cry out for more genre descriptors: they’re dark fantasies, satires, comedies, period pieces, gothic tales, thrillers. In a diverse body of work, his distinct artistic personality never fades. Herz horror films are unstable, larger than life. They’re shot with an expressive, inventive, mobile camera. Their visuals are surreal, unreal, and flamboyant—from the sets, to the costumes, to the hair and makeup. There’s an offbeat sensibility, an air of dark comedy, to most of the oeuvre. There’s an ever-present interest in sexuality and the appetites. There’s an eye for the grotesque. Herz horror films are unmistakable.

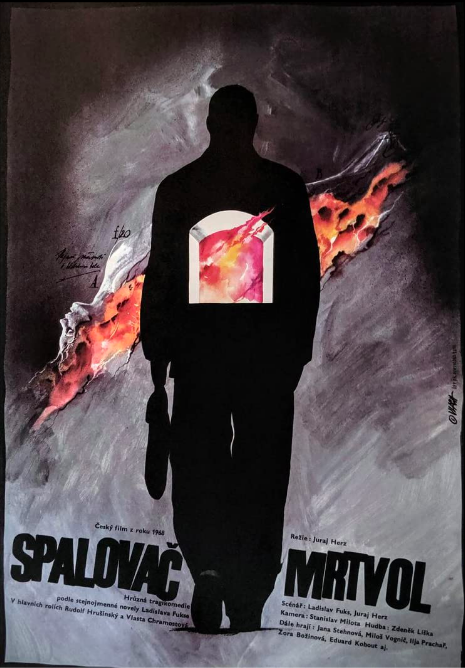

His horror career is bookended by films about the Holocaust. Herz, a Jew, was a Holocaust survivor, interned at Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany as a child. The Cremator (1969), his second feature, his enduring masterpiece, and his easiest film to see in the U.S., offers a provocative, volatile surface—disorienting close-ups, surreal visions, actors in multiple roles—that makes a macabre nightmare of wartime Prague. The Cremator engages the history with the particular, peculiar vision of artists who actually endured fascism (Vladislav Fulks, who wrote the novel, was a forced laborer under the Nazis). The Cremator tells the story of how a deranged man uses fascism and how fascism uses him. A dark comedy but a film of such rising dread and tension, culminating in an excruciating final half hour, that the horror is what lingers at the end. A film about the war, but also a film about indulgence, about vulgarity, about megalomania.

Darkness (2009) (or “T.M.A.”), his last horror film, also engages with the history of the Holocaust, but in a more standard, cinematically familiar way. Here we have a haunted house tale, with a small town’s war history, and the atrocities committed in the central home, as background and curse. (This being a Herz film, there’s also an intertwining story of sex and jealousy). Staid by comparison with his other horror movies, Darkness still looks and feels like Herz. Genuinely creepy if never really scary, its protagonist's warped, nightmarish paintings bring in something of the dark fantasy visuals of his other movies.

The film that sits alongside The Cremator as the other Herz classic, Morgiana (1972)—indeed, the work of his that seems to be chattered about in cinephile circles the most—is a film of pure, utter excess. In Morgiana a jealous woman (Iva Janzurová) plots the murder of her sister (also Iva Janzurová) and the hallucinatory gothic melodrama that follows is unrelenting: we get doubles, visions in mirrors, opulent sets, garish makeup, giant hats and wigs, wild color-juiced shots, and a cat’s POV. In this near-bursting world, one crime precipitates further transgressions—becomes a point of no return into psychic turmoil and violence. The quintessential Herz horror film.

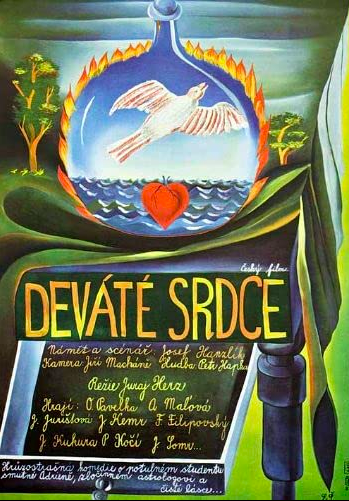

Herz went on to direct two horror fairy tales, one after the other. The second doesn’t match the first in style or effect, though it’s an interesting, at times visually arresting piece. This film, The Ninth Heart (1979), follows a young man’s attempt to deliver a princess from the power of an evil astrologer. Standout features are a clock-inspired set (complete with swinging pendulum) and an invisibility cloak-assisted prison break. Notable as a collaboration between Herz and surrealists Jan Švankmajer and Eva Švankmajerová. (Check out their wonderful opening credits sequence here. Read about Eva Švankmajerova’s art and poster design, including for this film, here). I could not find a disc with English subtitles, so I watched this in Czech, a language I do not speak. I had a good time anyway.

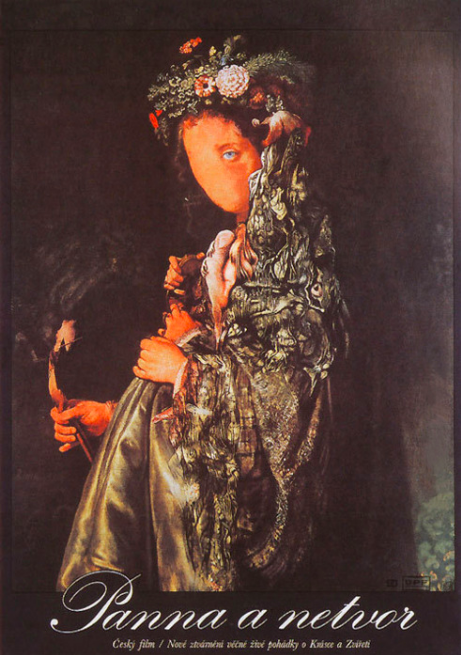

The real “discovery” (to me at least) in all my Herz screenings was Panna a netvor, translated into English as Beauty and the Beast (1978) but translating directly from Czech as “The Virgin and the Monster.” A recognizable retelling of the Beauty and the Beast story but with its own world and story, it’s a gorgeous, moody, horror fairy tale. The beast here is scary, murderous, and looks—surprise—like a bird. Herz uses the forest as a mood-setter—a spooky, immersive setting that encroaches into the interior of The Beast’s enchanted mansion. Herz’s film would make a good double feature with the classic Cocteau.

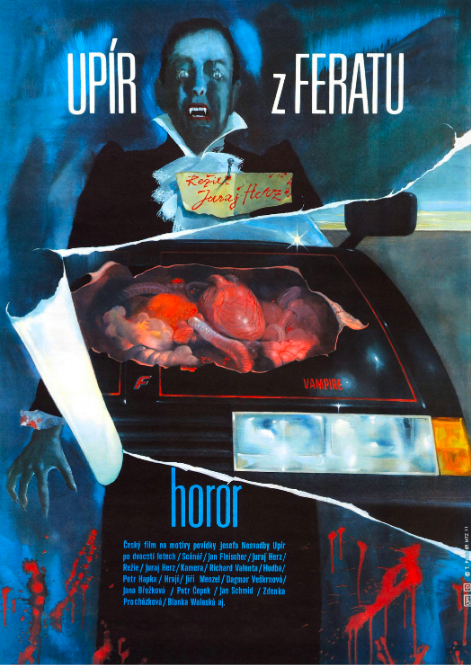

The curio in the Herz horror filmography, Ferat Vampire (1982) does not lend itself to easy description. It has much in common with a 70s conspiracy thriller—an out-of-his-depth doctor gets wind of a sinister secret and embarks on a solitary, dangerous hunt for answers. The conspiracy though? An auto company’s fastest race car maybe runs on human blood. Ferat Vampire is not a comedy, but there’s a measure of humor here, a satirical lens on 80s capitalism, and Herz’s doctor certainly knows that he’s investigating something absurd. If Ferat Vampire does not quite fulfill the expectations of its genres—the film is not scary or tense—it stands out as something strange and oddly compelling. Its villains are especially watchable—their office interiors and outfits giving Bond villain, or maybe fashion house, or maybe sex club. And there’s the woman in charge of the company—always petting a gorgeous assistant like Blofeld would a cat. Although its surreal premise is underutilized—we mostly get a doctor asking questions and sneaking around, Ferat Vampire does feature an unforgettable “vampire car” dream sequence: something straight out of A Nightmare on Elm Street (two years before Freddy first arrived in theaters).

Unfortunately, Herz horror films are not always easy to watch. Here in the U.S., The Cremator is available on the Criterion Channel and on a Criterion Collection disc. I watched the rest on discs ordered from the UK or Europe. And The Ninth Heart, as mentioned above, is not—as far as I can tell—available anywhere with English subtitles.

So what to watch? The Cremator, Morgiana, and Beauty and the Beast are unmissable. The others are interesting, and completists will have a good, sometimes frustrating, sometimes trippy time with them. The rest of his filmography, the non-horror stuff, I have yet to sample and is going on my own watchlist.

Dead of Night has no publication schedule. Sign up to receive new essays about horror cinema in your email inbox.