Frail Minds | Cure

Watching closely, losing yourself.

Film discussed: Cure (1997). Major spoilers. I'm usually quite chill about spoilers, but for this film I strongly recommend watching before reading. It's streaming over on The Criterion Channel.

Content warning: murder, violence, mental illness, suicide.

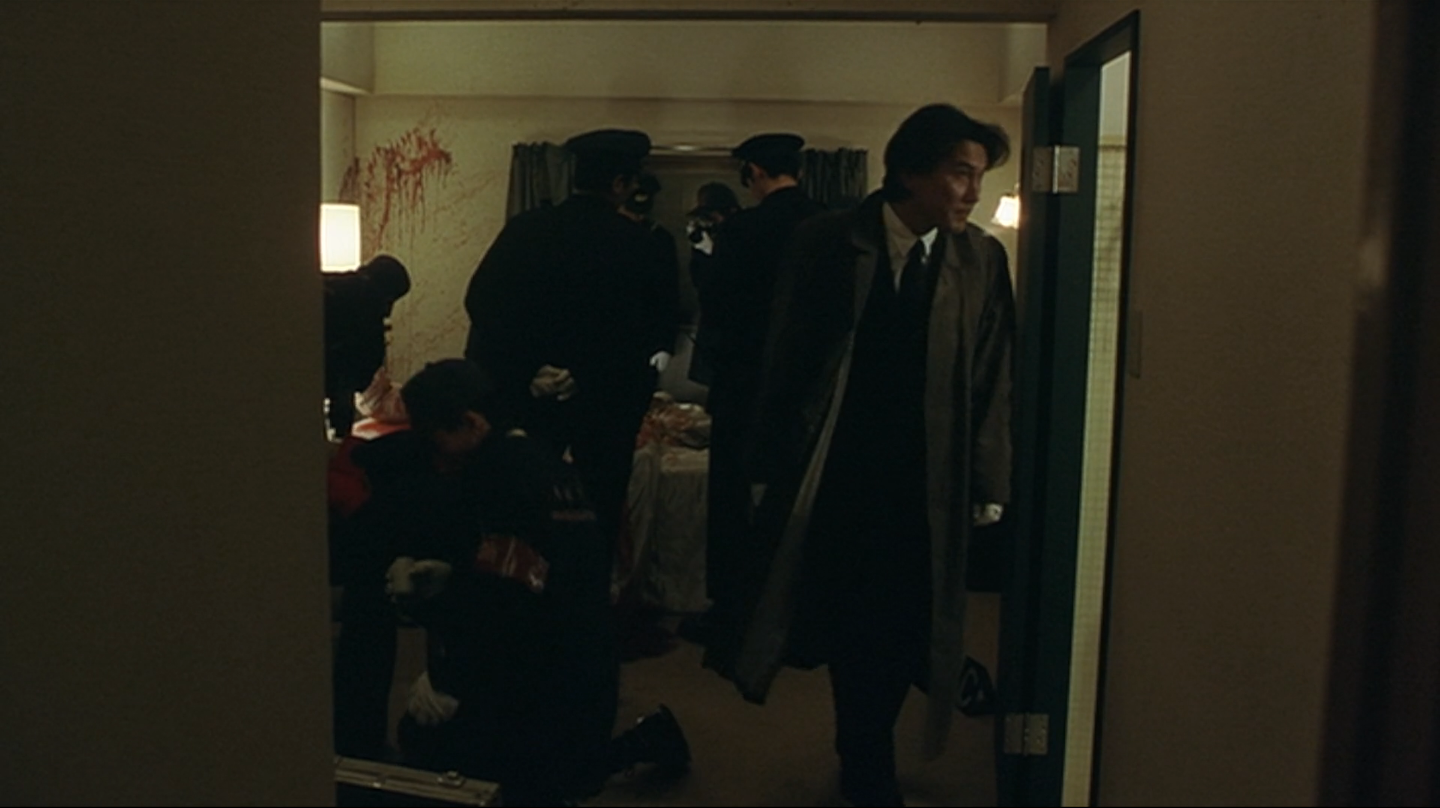

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997) has all the familiar markings, as it begins, of the serial killer film: bizarre, gruesome murders; an angsty, trench coat-clad detective; a race to catch the killer as the body count grows. The case Detective Kenichi Takabe (Koji Yakusho) investigates—random murders by different perpetrators, each unable to explain their actions, a tell-tale X carved into the neck of each victim—has enough high-concept style to set up a solid, ninety-minute thriller (or a compelling hour of procedural TV). And, in many ways, Cure is just this kind of serial-killer story. The gore, the dread, the puzzle-like quality of the crimes, the obsessed detective—these all conform neatly to our expectations.

Though perhaps the different perpetrators detail hints at the fact that Cure is on its own, unique wavelength. While we can imagine a more traditional film with just this type of unnerving set-up, it provides a complication for a subgenre in which a film’s gaze is usually directed at a single, dark mind behind the mayhem. As Cure begins, Takabe is less following a trail of murders than a trail of murderers. There’s a mystery of motivation and explanation here. There’s no doubt the killings are linked. But how? Why? Almost any explanation strains credulity.

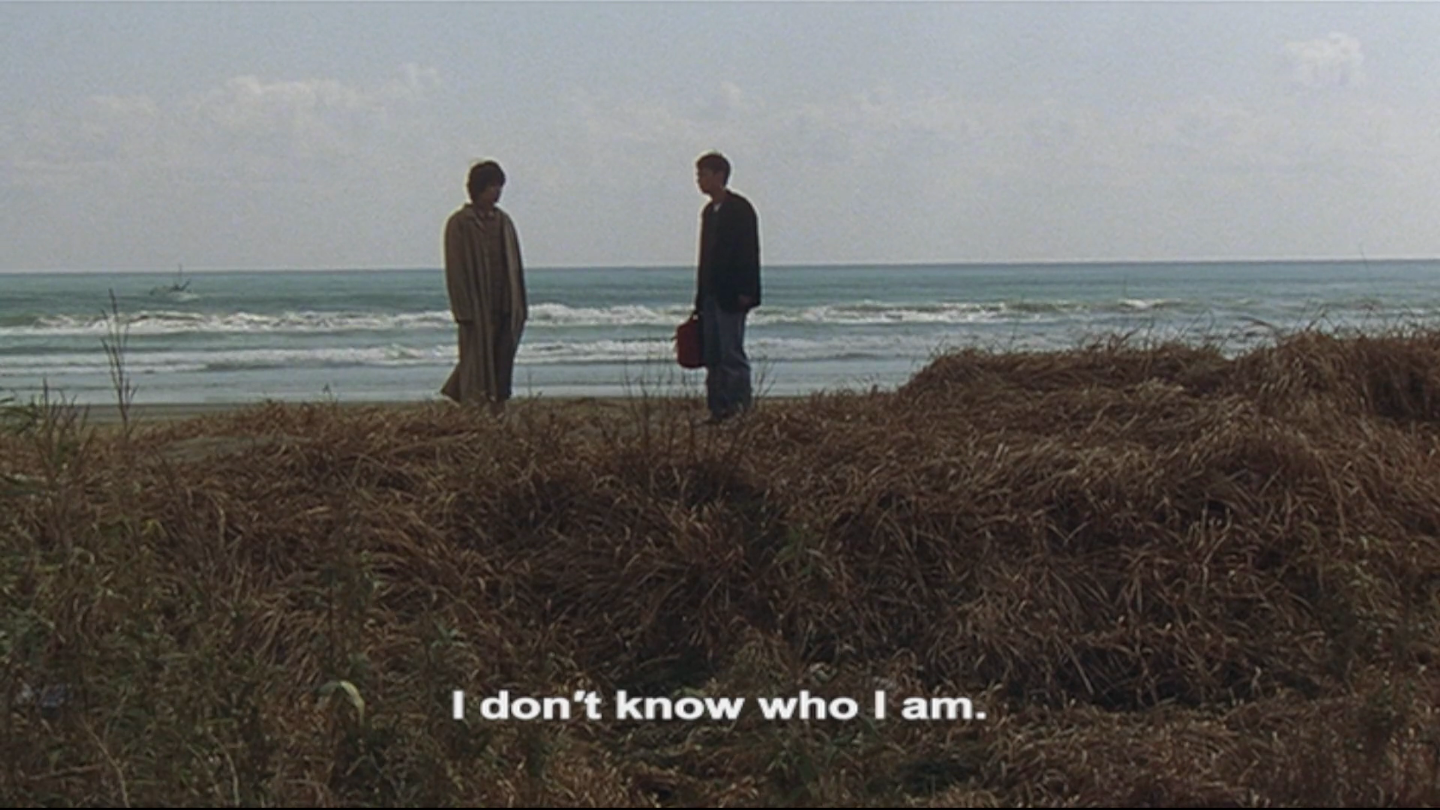

Kurosawa does not withhold the resolution of this question very long, but instead sows new, equally vexing complications as we meet the man behind the killings. Kunio Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) has spoken to each of the perpetrators shortly before they kill. He seems to be able to hypnotize them. We start to follow Mamiya well before Takabe identifies or arrests him—again, not an unusual approach in a serial killer film. What we don’t get is a recognizable type of predator. Mamiya is not a lurking, heavy-breathing creep or a charming, calculating sociopath. He has no identifiable vision really—at least not of the post-Thomas Harris variety where some absurd but coherent project underlies a killer’s crimes. When we first encounter Mamiya—meeting a soon-to-be victim/murderer (I'll continue to refer to the hypnotized as Mamiya's "victims" in this piece) on a beach—he doesn’t know where he is. He doesn’t know the date. He doesn't know who he is. When asked where he’s going, he replies, “nowhere.” He comes across as vacant—a man with no short-term memory or identity. He seems perpetually confused, dazed. He’s impossible to have a conversation with.

No one’s as frustrated by this diversion from genre conventions as Detective Takabe. He expects, as an audience might, some resolution when Mamiya’s captured—not merely of the cause of the crimes, but of their meaning. Takabe tells the consulting psychiatrist Makoto Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), “All I want is to find words that explain the crimes.” When Takabe finally gets him in an interrogation room, Mamiya can barely answer a single question. He doesn’t recognize a picture of himself. He answers Takabe with questions of his own. He drifts around the room. Sakuma winds up restraining a fed-up Takabe as he rushes at the prisoner. Later, in the adjoining room, Takabe splashes a cup of coffee at the image of Mamiya’s face in the one-way mirror. Takabe wants a killer. He’s got something else—something opaque, incoherent, illegible. Instead of encountering the mind behind the crimes, he’s encountered almost no mind at all.

It would be less unsettling if Mamiya’s fog was a strategy, something faked. Takabe, and the genre, would find it easier if he was just a serial killer hiding behind faked amnesia. And it’s never clear, exactly, if he is faking anything. He certainly acts with purpose to hypnotize his victims. He does convey, despite his fog, an air of menace. He’s capable of turning around one of his trademark vague questions, repeating it as a philosophical pun aimed at his interrogator. In one scene, his “who are you?” evolves from a simple question of identity to, when he repeats it, something more piercing. He wants to know something deep, something essential. He's asking, really, "who are you?" It all conveys a sense that there’s more to Mamiya, something behind the fog, but no mask ever comes off.

The closest we maybe get is an enigmatic moment, after Mamiya’s shot, when Takabe asks him, “Do you remember everything?” He nods yes. But the cryptic exchange does not quite change our perception of the man. He’s given us hints all along that there is something fundamentally different, even inhuman, about himself. In one of the hypnosis scenes, he says to his intended victim, “All the things that used to be inside me, now they’re all outside.” He also tells her, “I can see all of the things inside you, Doctor. But the inside of me is empty.” Later, when he’s working his hypnosis on Takabe, he says, “The water will make you calm. It will make you happy, empty. You’ll be born again just like me.” In these lines, Mamiya comes as close as ever to telling us about himself. He’s somehow “empty.” He’s perhaps not a person in the ordinary sense. There’s something there. Something malevolent. Maybe a kind of “missionary” of early hypnotism as Sakuma says. But not quite a recognizable human. Mamiya is less a man with a dark design than a dark design made flesh.

His crimes also challenge our understanding. Mamiya’s hypnotisms are nothing spectacular to behold. A vague conversation culminates in a lighter being struck or a glass of water being spilled or rain dripping from the ceiling, and his victims are suddenly still, entranced by the light or the shimmer. Then Mamiya typically asks a question (e.g. “I’d like to hear about you.”), and, with one exception, the film then cuts away. These are scenes that depict a powerful, almost magical force arising within the mundane, casual flow of ordinary life. Something in Mamiya’s voice, behavior, words, the trick of the light from flame or water—something is giving him power over these people. But it’s never clear what exactly the mechanism really is. This is, of course, the popular perception of hypnotism (and maybe the reality of it?). It’s subtle, something that catches you unaware. Cure establishes a world in which small, seemingly unimportant minutia can reach out and grab hold of you. It’s a world in which our perceptions can’t be trusted, in which a dark, imperceptible mysticism suffuses the mundane.

Not only is the technique of Mamiya’s crimes a mystery, what’s happening psychologically to his victims is too. Mamiya is influencing them to commit murder and to carve the tell-tale X into the neck of the murdered, and it’s quite clear that without Mamiya’s intervention these murders would never have been committed. Each victim, after killing, cannot explain their actions coherently, their emotional reactions ranging from befuddlement to anguish. Mamiya is no doubt the responsible party. Even so, Kurosawa does not quite allow us to view these killers as entirely blameless, as mere tools, as uncomplicated good people hijacked by hypnosis.

In an early scene, Takabe waits in line next to a man at the dry cleaner. As the man waits for his clothes, he mutters angrily to himself, in some imagined argument with a “dumb shit,” probably someone at work. The muttering ceases as the dry cleaner returns, and he’s perfectly cordial as he receives his clothes. He’s a figure of simmering wrath, buried beneath a socialized persona, and he may just be a model of the human minds prevailing in Kurosawa’s world. He’s something of a clue—one of the first—that the people Mamiya’s inducing to kill might be unlocked more than simply controlled.

When mesmerizing his victims, Mamiya’s asking them about themselves, about their lives. “Tell me more about your wife?” he asks one. “Now tell me about yourself,” he prompts another. While he must be implanting ideas (like the X), he also appears, perhaps, to be learning about them, teasing out their inner lives. After a policeman is induced to kill a coworker, the police question him, and he’s forthright about his feelings about the guy. While he can’t explain his abrupt, calm execution of the man, he says he killed him because he didn’t like him. “It’s been three years since he was transferred to our box. I put up with him all the time. Finally I couldn’t stand it anymore.” Takabe asks him why that would prompt a murder, and he replies, “. . . [Y]ou’ve never killed anyone have you? That’s how you get when you hate someone from the bottom of your heart.” From the sound of things, the murder may have been triggered by the hypnosis, but the motivation was already there.

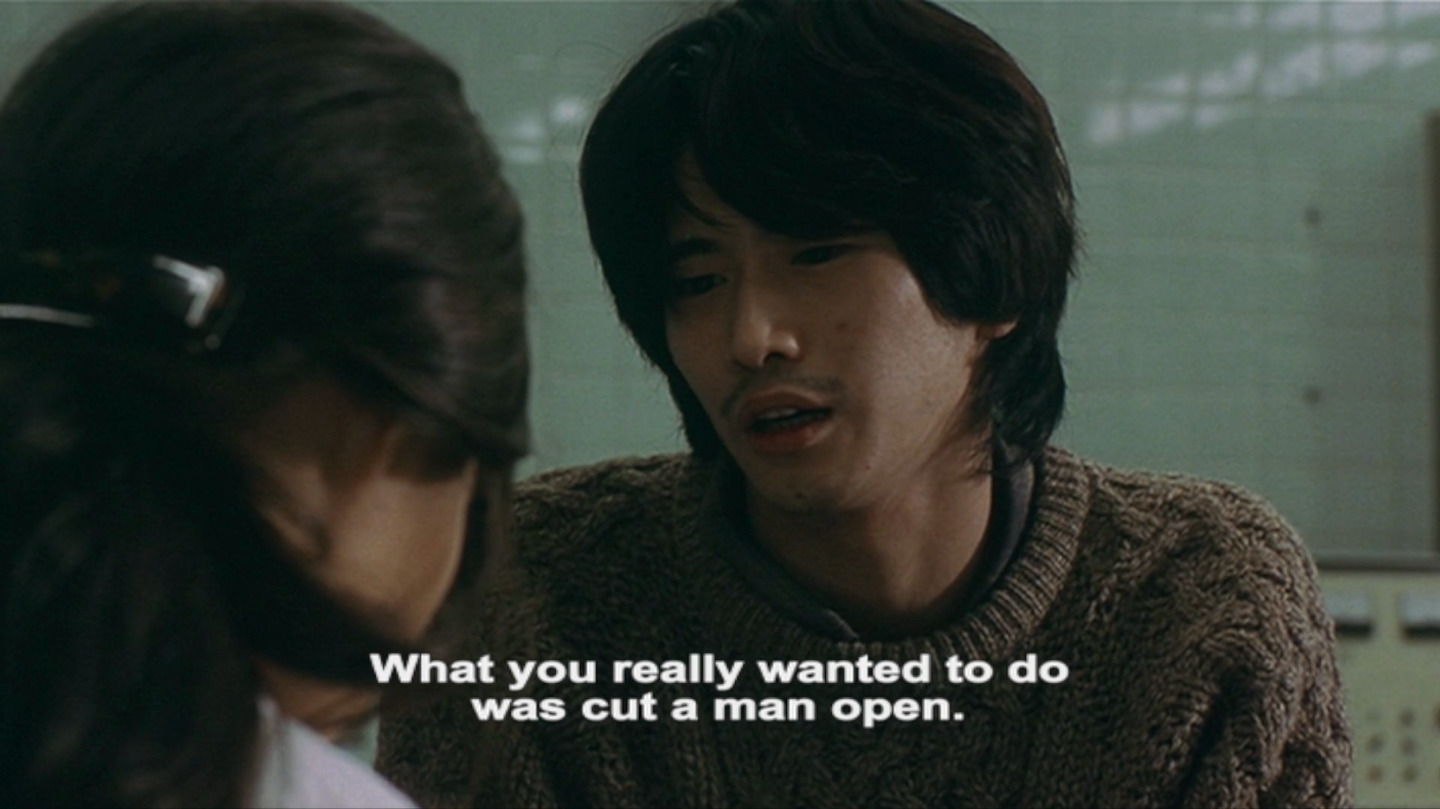

Though not all of Mamiya’s victims reveal themselves this way. And the most involved hypnotism scene leaves some doubt about what’s being drawn out and what’s being implanted. Mamiya’s in the hospital and left alone with a doctor. He hypnotizes her with a spilled glass of water and, unlike the other hypnotism scenes, we witness his entire interaction with her. It’s a kind of dialogue, but one-sided, the entranced doctor repeating Mamiya’s words a couple times, shaking her head once, but mostly listening as Mamiya talks. He describes sexism she’s faced, describing people saying to her, “You’re just a woman. Why did you become a doctor?” He talks about her dissecting a corpse in medical school—how it made her feel good to cut into a man. How she originally wanted to be surgeon so she could cut men open. It’s an interaction in which memory cannot be distinguished from suggestion. Much of it sounds plausible, even likely, though the cutting men open bit maybe sounds more like Mamiya's notion than hers. She seems to accept what he tells her, repeating “Just a woman” back to him when he asks her to remember it. But she’s in a trance. There’s no way to know what’s really already there inside her mind. Mamiya told her earlier, “I can see all of the things inside you, Doctor.” Maybe he can?

Victim psychology is a mystery in Cure but not a complete one. Takabe’s own journey should make us confident that, to some extent, Mamiya is finding what he needs waiting for him in his victims’ minds. When we first meet Fumie Takabe (Anna Nakagawa), she’s reading a Bluebeard story, and Cure turns out to tell the story, subtly, almost imperceptibly, of Takabe killing his wife.

Takabe is a man struggling with his wife’s declining mental faculties. She gets lost in the city, leaves raw meat for him at the dinner table, forgets things. In many ways, he’s a model husband—but it’s clearly a strain. He tells Sakuma that she’s doing well, but then admits that he doesn’t actually know. As the Mamiya case gets more and more stressful, Takabe finally puts her in an institution, intending to bring her home when the case is over. During a tense confrontation with Mamiya in his cell, Takabe unburdens himself: “I spend my whole life taking care of that wife of mine!" Like most primary caregivers of people with serious struggles, he’s doing a good thing, but he feels a measure of stress and resentment. He would never, of course, think of harming her.

That is, Takabe never would have thought of harming her until Mamiya insinuates himself into his mind. It seems to happen gradually, and there are several scenes in which Takabe encounters hypnotic suggestion. There’s a hypnotism scene in Mamiya’s cell, with dripping water catching Takabe’s attention. There’s the X Mamiya gestures in the air as Takabe watches him die. There’s an old phonograph recording Takabe listens to, found in the old building where Mamiya dies, seemingly conveying a hypnotic message. Mamiya seems to be trying to make Takabe—not one of his usual victims—but a “missionary” like himself. A hypnotizer. In the hypnotism scene, he tells Takabe he’ll be “empty,” just like Mamiya. He says Takabe will be “. . . born again, just like me.” Later, in a hearing with other police, he tells Takabe, “They don’t understand do they? About me or about you.” He’s molding Takabe in his image.

The success of Mamiya’s hypnotism reveals itself in two blink-and-you’ll-miss-them moments at the film’s end. First, we see, for a quick instant, Fumie Takabe dead, an X slashed into her throat. Then, in Cure’s final, astonishing scene, we see Takabe in a cafe. Nothing appears amiss, as we get a wide shot of his server leaving his table and going about her duties at the restaurant. Then we see her, if we’re watching closely, deep in the shot amid the clutter of the dining room, pull out a large knife, the scene ending almost as soon as we get a glimpse. She must be, in the world this film has developed, about to kill. It seems that Mamiya’s finally gotten through to Takabe. Takabe’s induced this server to kill. And he’s killed his wife (or hypnotically induced someone else to kill his wife?).

It’s been uncertain, as with the doctor, whether Mamiya was harnessing inner darkness or implanting it. But Takabe's evolution into a wife killer sends the strongest single that it's the former. We know Takabe has an inner darkness. He loves his wife, but she drives him crazy. She's the ever-present, primary difficulty in his life—since long before he ever meets Mamiya. Under Mamiya’s influence, his darkest mental spaces are channeled, liberating them from the strictures of conscience and socialization. Mamiya may be warping the minds of his victims, but he’s harnessing a darkness that’s already there.

The precise vision of human experience in Cure is something to debate or to arrive at delicately. Cure’s enigmatic, withholding surface is an important part of its power. Early in the film, Sakuma says, “No one can understand what motivates a criminal—sometimes not even the criminal.” And questions of mind, motivation, and behavior remain mysteries. Are we figures of contained, simmering rage? Or are we more balanced creatures, our darkness contained in its proper place unless unleashed by a sinister force? Either way, there’s no doubt that the darkness is in us, we’re capable of great violence, and the world is not dependable. If some subtle combination of voice and light can make us monsters, then we can’t quite trust ourselves. Takabe has lost himself entirely.

We’re consistently in Takabe’s predicament throughout, unable to trust ourselves. Cure wants us to experience its world as much as witness it. It favors long, bold takes—takes that develop meaning and effect over time, asking us to hold our gaze, waiting for more. We get quick shots of the visual tools of hypnosis: flashing lights and flowing water. We get sudden flashes of a ritually killed monkey, of Takabe’s wife, of a knife being grabbed. And we get whole visions. Takabe finds his wife dead, hanged in their home. Sakuma finds himself outside the building where Mamiya dies, someone staring out at him from the inside. Then we see him in Mamiya’s cell, where we see (again) a ritually killed monkey and then Takabe approaching him menacingly. These are all only revealed as visions after we experience them. Their recurrence destabilizes reality. We can justifiably ask, at any moment, “is this real?” The grammar in Cure—long takes, quick takes, real, unreal—never lets us relax. We find ourselves in an uncertain, untrustworthy world, plagued by what we might be missing, by what we’re failing to grasp.

Sakuma shows Takabe an old film on hypnotherapy from university archives: “The oldest material on hypnotism in Japan.” It’s unremarkable, short footage of a woman and a mostly unseen hypnotist. But Sakuma slows the video down, and, as they watch the slowed video, they can make out the hypnotist drawing an X in the air with his hand. As they watch, Sakuma says to Takabe, “You have to look closely,” and he might as well also be instructing us on how to watch Kurosawa's film. For the archival footage presents a viewing experience not unlike Cure itself: a subdued, objective frame, a pervasive sense of secrets hidden within, the secrets only revealing themselves—barely, suddenly—if we watch closely.

If there's a distinct kind of horror in Cure, it's perhaps about the frailty of the mind. We can barely make out a human mind in its villain. We find a world of people whose minds are breakable, who are susceptible somehow to whatever darkness is contained in them. As viewers, our eyes strain at the screen, seeking coherence, seeking the vital detail, never certain that our own perceptions can be trusted, that our own minds are up to the task.

Horror writing elsewhere

I've been catching up on gialli these last couple months, watching (among others) The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh and The Red Queen Kills 7 Times, both for the first time. I was pleased to come across this article by Rachael Nisbet about the role and significance of the showstopping modernist apartment Casa Papanice in both films (and in Dramma della gelosia). And it really delivers—exploring the spatial and visual design of the apartment and its thematic and cultural place in each film. Check it out!

Dead of Night has no publication schedule. Sign up to receive new essays about horror cinema in your email inbox.