Eyes in the Dark | Watcher

Through windows and cameras.

Chloe Okuno's Watcher is one of my favorite horror releases of recent years. An elegant, scary directorial debut—in a beautifully moody Bucharest—it's a movie I love to recommend. Rewatching recently, I started thinking about what it means to be watched and what this has to do with cinema.

Definitely some spoilers for the movie, so watch it first if you need to.

Content warning: Stalking, voyeurism, serial murder.

Voyeurism is the sexual fetish most central to cinema. This is a well-worn topic in film criticism, where the discussion tends to focus on audience and filmmaker. A film audience peers into the intimate lives of characters, watching their sins, their private moments, their romances, their tragedies—and, for sure, simply gazing at the faces and bodies filling the screen. Figures on-screen are voyeuristic objects, on display for camera and audience (a gendered dynamic—Laura Mulvey the foundational theorist). Cinema is an art form that we watch, so it’s unsurprising that we think, a lot, about what it means to watch. We’re even more unsettled when we think about the experience of watching in horror, where we’re often seeing, either directly or not, through the predatory eyes of monsters and killers. What we think about less in this dynamic is what it means to be watched. This is not a small thing, especially for actors—those on the receiving end of the gaze.

Watched

Watcher follows a character who’s constantly watched. In Watcher, Julia (Maika Monroe), an American newly relocated to Bucharest for her husband’s job (husband Francis played by Karl Glusman), becomes aware of a man in a nearby building watching her through her apartment windows, all while a serial killer stalks the city. It’s a basic setup not new to thrillers or horror movies. What’s distinct is the film’s minimalism, its stripped-down attention to Julia, mostly alone, in her apartment or in the streets of Bucharest, grappling with the looming presence of her watcher. Its close, subjective tie to Julia allows the weight of the oppressive gaze to fill the cinematic space. Watcher explores and inhabits the experience of being watched.

Being watched changes behavior. Julia, as soon as she spies the man watching her, is looking back, monitoring her surroundings, gazing fearfully out the window. Even the shadows inside her apartment require examination. Watched become watcher and watcher becomes watched.

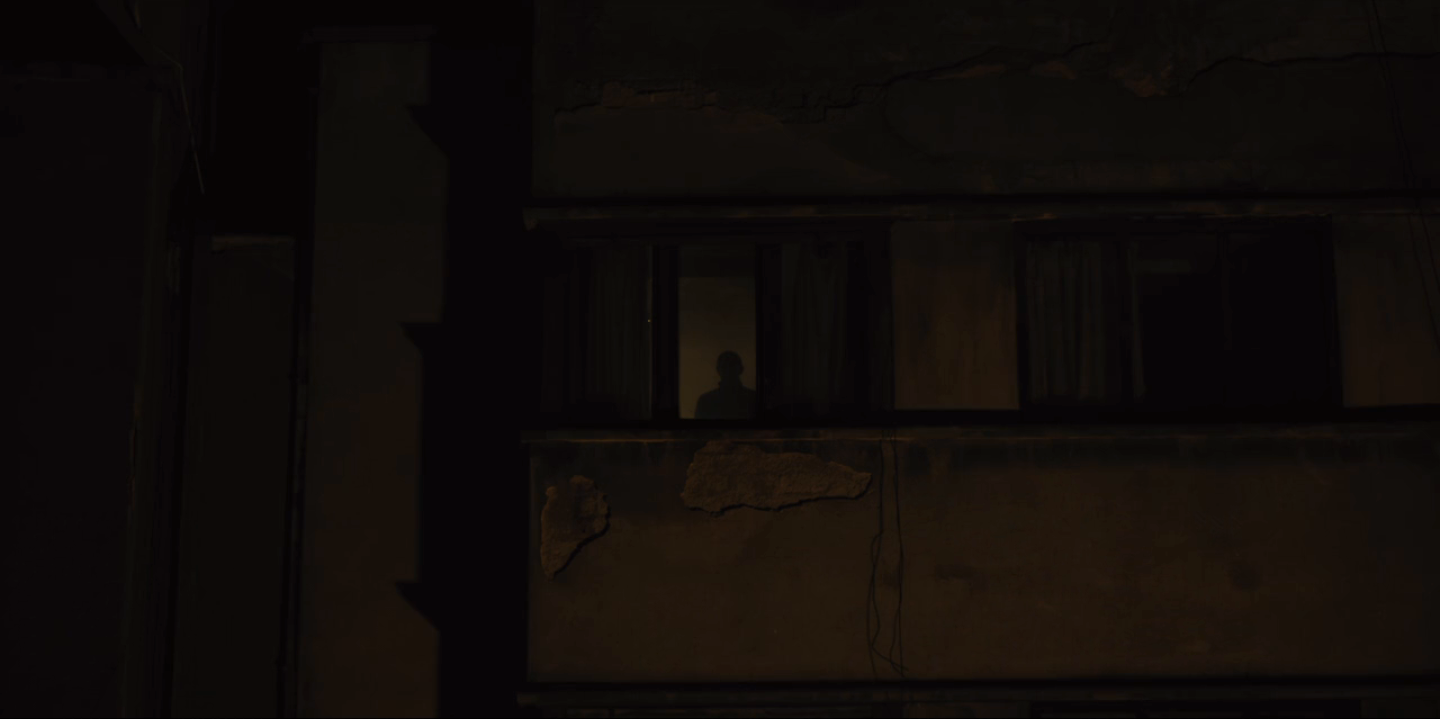

Despite the two-way nature of the relationship, the fundamental roles (and moral charge) do not change. The watcher remains the uninvited aggressor while Julia watches back defensively. Julia's in a rather impossible position. About midway through the film, she pulls aside a narrow gap in her window curtain to peak through, dropping it instantly when she sees the now familiar silhouette in the window across. What's she to do? She can ignore him or she can interact. If she ignores him, he might eventually quit, but things might also continue indefinitely or, perhaps more likely, escalate. Interacting could scare him off but could also trigger immediate escalation. It offers the possibility as well of granting her some insight into the man's frame of mind, and whether he is, in fact, watching her (she’s mostly seen him as a featureless shadow). Each option is unpleasant.

She decides to interact. “Fuck this,” she says, flinging open the curtain, and there he still is in his window. “You’re not really looking in here are you?” she asks, hoping. Then—to confirm—she waves. When there’s no immediate response we see the relief on her face. But then he waves back and dread replaces the relief. Julia’s decision to interact has confirmed that he’s watching her. They’re both watchers, but only one by choice—the other’s made contact with a creep in a city haunted by serial killings.

The trouble with being watched is that what’s disturbing in one light is invisible, meaningless in another. The situation fills Julia with anxiety but, for others, like Francis, it doesn’t always come across as particularly threatening. Watching is passive, after all. There’s a plausible deniability to it. The invasion we feel from another’s eyes turns largely on context, on situational expectations, whether in private or in public. An unsettling image we get is a quick POV shot of the back of Julia’s head when she’s sitting in a cinema. She’s ducked into the cinema only to have her watcher show up a few minutes later and sit down right behind her. A quick glance over the back of the head is unremarkable—something expected in a movie theater. What’s upsetting about the shot isn’t what he’s seeing but the sense that he’s come not to watch the movie but to watch her. In a cinema we expect to be seen, we don’t expect the close scrutiny. We don’t expect to be watched.

Our expectations about who’s watching, and when, depend on our individual, subjective realities. Julia eventually follows her watcher, tracing him to the strip club where he works as a cleaner. The club itself is a kind of monument to blurred expectations: tucked away, without signage, in the basement of an unassuming building, the dancers mostly separated from the patrons by barriers—but glass ones. She stumbles across her neighbor Irina, a dancer, and asks her if she, too, has noticed the watcher. “No,” she says, “But maybe I’ve gotten used to having eyes on me.” Irina’s world brings with it a different set of expectations. She spends hours openly looked at by a room full of eyes. While she’s naturally entitled to the same privacy in her apartment as Julia is, her experience of a stray gaze from a nearby building has none of the effect it does for her neighbor. It doesn’t even register.

Being watched disturbs partially because it feels like a prelude—a sense of something coming, some escalation—so it draws out its target’s general sense of safety and security. Julia’s a newcomer to Bucharest and Francis is busy—gone for long stretches of time. What Julia might have experienced as that pleasant sense of anonymity and discovery in a new place instead feels like isolation and dislocation. The feeling of being watched, of being targeted, draws out the degree to which we’re at risk.

The distinct factor here is power. Julia’s a white American, she has a lot of power in certain ways, but here, newly arrived in Bucharest, she finds herself on the disempowered end of several divides—of nationality, of language, and, most potently, of gender. As the watcher circles in on her, Julia’s bids for assistance from the men around her are consistently futile. The policeman she turns to is useless, ultimately entertaining the watcher’s assertion that she’s the one stalking him. Francis wants to be supportive, thinks of himself as supportive, but becomes increasingly more bothered by her behavior and attitude then the real fact that a man is stalking her.

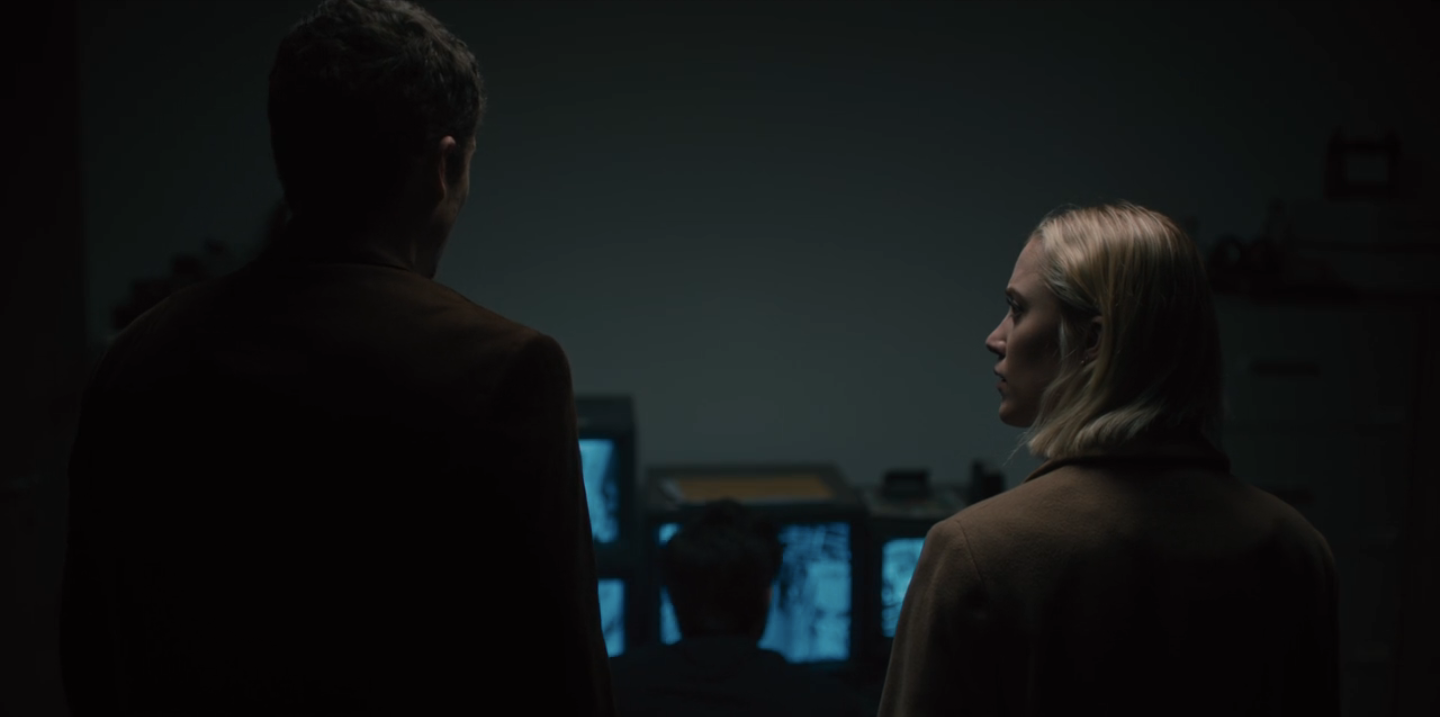

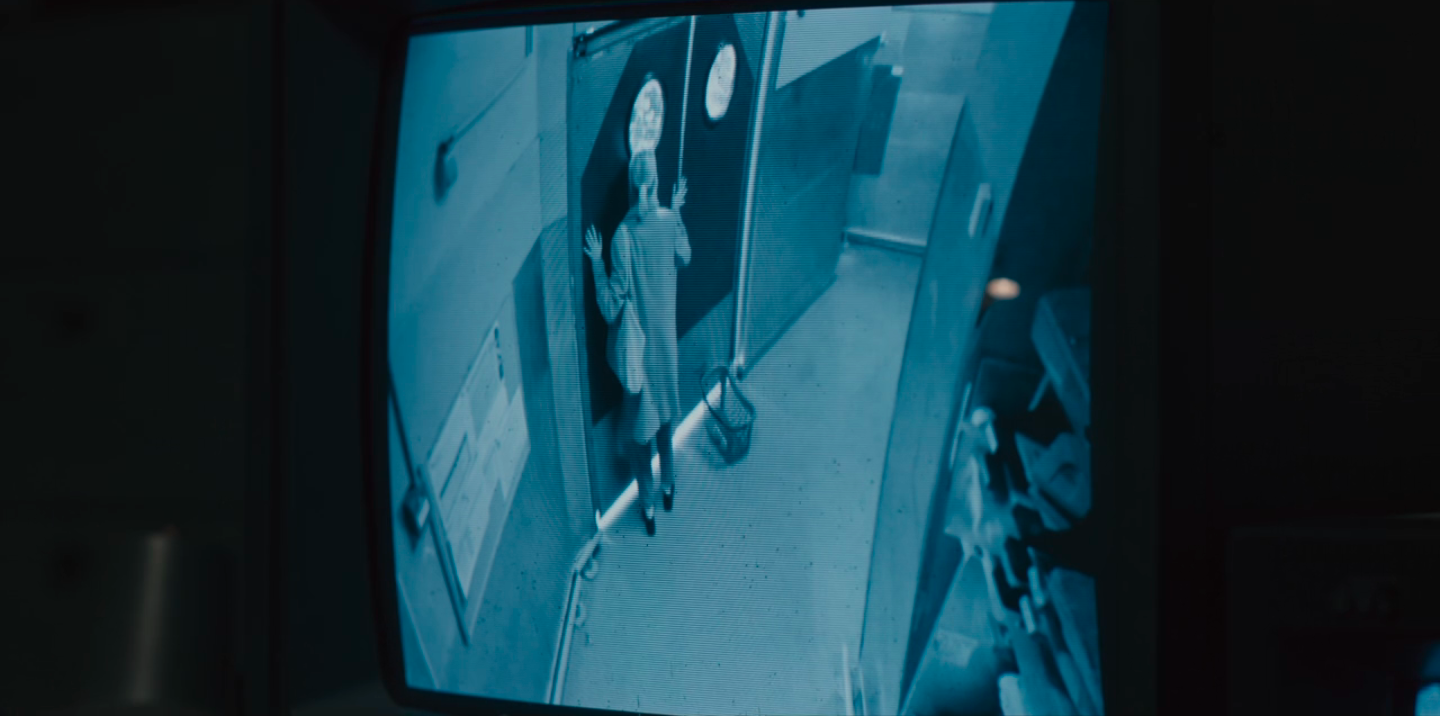

Julia’s embedded in a gendered power dynamic that structures her entire experience when, after the watcher follows her into the movie theater, she flees to a grocery store. The watcher, naturally, appears in the grocery soon after. Shaken, Julia tracks him as he paces around the store, loses sight of him and, catching sight of him again, backs away into a shelf of pickles, sending a jar falling and smashing on the ground at her feet. She retreats into the grocery’s back room, watching through a porthole-style window as the watcher steps up to the broken glass. When she’s interrupted by a suspicious grocery worker she escapes out the back.

The next day she goes back to the store with Francis and they ask to look at security camera footage. Though the grocery employee (the same one from the day before) says he had thought she was trying to steal, he lets them review the footage. On the tape, though, the watcher’s threat doesn’t really read. He’s just a guy in the store—a guy inspecting the broken jar of pickles. “There,” Julia says, “See. He’s staring right at me.” Francis sees it differently. “. . . maybe he’s staring at the woman who’s staring at him.”

Julia’s learning that noticing being watched—for a woman, at least—is itself a kind of norm violation. The subtle, plausibly deniable invasions of watching or following someone don’t raise alarms even when framed by the woman its happening to. Her reaction to the invasions though—knocking over a jar, hiding in the back and peaking through a window—look, to the men she’s dealing with, suspicious, even unhinged. The grocery worker sees a thief in a woman in distress. Francis sees a fantasist, a neurotic.

These perceptions might be unfair, but they aren’t huge stretches or distortions. Julia does look kinda wild hiding in the back peeking through a window. There’s not much to see in the security cam footage but a woman backing into a shelf of pickles. And people do sometimes believe themselves targeted when they are, in truth, imagining things. The watcher’s aggression finally only registers if we see objective reality in Julia’s subjective account. This requires a worldview in which her story feels plausible. Is it any surprise that her only true ally in the film is another woman—Irina?

Actors

If Watcher models the experience of being watched, of being on the receiving end of the voyeur’s gaze, what might it tell us about the condition of the actor in cinema? To be watched on-screen is not to be watched in the real world, in the home and on the street, but the screen actor’s experience—before the camera and in the cinema—is, like Julia’s, an existence shaped by eyes in the dark.

The actor does not, when subjected to the gaze, become a watcher herself. She is separated by time and technology from her audience. But she does always apprehend the watcher. An actor cannot look back, but her world is constantly shaped by the pull of the camera and the eyes that will eventually receive its vision. The actor, unlike Julia, is there, watched, by choice. But she is similarly locked into a fixed dynamic. There is no uninvited aggressor and no victim, but there is an anonymous, faceless sea of eyes. An actor on-screen is forever the watched and we, the cinematic audience, are forever the watchers. There may be a power in performance, in commanding attention, but there’s a power too in passive consumption—unseen, un-judged, unencumbered by expectations.

Julia has two bad choices—ignore the watcher or interact. An actor, ever-monitored by her audience, does not have this choice. She can only really ignore. This is her job. An actor expects eyes but portrays characters who don’t. Modern screen acting is to perform nonperformance–to be Irina but portray Julia.

It’s probably a mistake to think that actors, because they consent to—even seek out—the camera’s gaze, are immune to a sense of invasion in being watched. Actors, like Julia, have a set of expectations about how they are watched. Where Julia might have expected casual glances in public and not the close scrutiny of the watcher, a screen actor expects a certain kind of presentation. She’s joined a particular type of project, read the script, has some knowledge of the film crew. She’s seen the movie in her mind and a significant deviation will mean revealing herself in an unexpected light to all those eyes in the dark. How could it not feel like a kind of invasion?

Putting oneself before the camera, then, requires trust. And the ability to trust—to depend on the cinematic machinery around her—depends on the same kinds of power dynamics (gendered and otherwise) that hinder Julia in her search for safety in Bucharest. An actor’s control over how she’s displayed, how she’s watched, turns on the strength and agency she wields in her world. There’s a good chance that, if she does have an issue with her depiction, it won’t read as a problem to others in the room. Industry powers will be Francis watching security footage, not seeing what she's seeing.

Julia found that noticing being watched was, for the people around her, itself a norm violation. What might an actor expect if she doesn't approve of how she comes across on-screen? Likely the same kind of unsympathetic stare.

Horror Writing Elsewhere

"Not least when used as cinematic devices, ghosts are polysemous in nature, in their capacity for allegory and their potential to activate various registers of temporal consciousness." Don't miss Dennis Lim's essay on ghosts in Film Comment, a tour through the possibilities in cinematic hauntings.

Dead of Night has no publication schedule. Sign up to receive new essays about horror cinema in your email inbox.