Dreams | A Nightmare on Elm Street 1-3 & Valerie and Her Week of Wonders

Valerie's visions, Nancy's nightmares.

Films discussed: A Nightmare on Elm Street, A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge, A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, & Valerie and Her Week of Wonders. Some spoilers.

Content warning: murder, violence, suicide, mental illness, & drug addiction.

Dreams in film can be unique sites of expression. Anything can happen in a dream. But they can also feel like cheap tricks. Dream sequences give filmmakers the freedom to do anything they like without accepting the narrative consequences. In horror, where genre conventions demand regular scares and bloodshed, we’re used to dreams as scare delivery vehicles, especially early on, where plot requirements can keep much of the real mayhem at bay until our story progresses. Dreams may be met with groans or laughs, especially when an audience gets ahead of the filmmaker—identifying the dream sequence before the gasping wake-up shot. We’re not always interested in watching when the havoc doesn’t really matter. A central role of dreams in horror—as a means of shoehorning in extra excitement (while, maybe, also illuminating a character’s interiority)—is undercut by the eventual reveal that it’s all just been a dream. They are shallow, kinetic fun, but their power dissipates when the dream ends (or earlier if the sequence gives away the fact that it's a dream). Even when the audience bought it, when they had a good time with it, they’re ready to get on with the movie. The real movie.

This dynamic is different, though, in films that focus squarely on dreams and dreaming. There still might be that audience question, “Is this real or is it a dream?” but unlike films set firmly in the real world, for films about dreams the stakes don’t diminish because we’ve left the real world behind. Dreams don't merely color the real world. They're the whole point. There’s an obvious “dream horror” franchise that comes to mind—one where the stakes heighten dramatically as soon as the dreaming begins.

In A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) the dreams are not always all that dreamy. The centrality of dreaming might have pushed Wes Craven toward the surreal, and the film has its share of fantastical imagery (later Elm Street installments, with bigger budgets, go further), but, generally, its dreams picture the real. The dream world is a dream version of our protagonist’s house, her street, and, of course, Freddy’s boiler room. The dream world is not a portal to an otherworldly dimension—some barren landscape of melting watches and semi-human forms—but instead to a world we recognize. The dream world, on Freddy’s Elm Street, seems to parallel, or duplicate, the real.

Its dreams also tend to share a continuity with the real world. Our final girl Nancy will, in her dreams, set off from right where she fell asleep. She’ll start in her bedroom, wearing the same pajamas she went to sleep wearing. She’ll also see, for instance, Johnny Depp’s Glen, who’s promised to watch her while she sleeps, disastrously sleeping in the chair by her bed. This is, in fact, what he’s actually doing. Real Glen, just like dream Glen, is a serious disappointment. Reality has a way of projecting itself directly into dreams.

This vision of dreams replicating and touching the real world does not conflict too much with our own lived experience. Dreams do tend to take place in our homes, schools, and offices. They’re populated by the people in our lives. They often feel continuous with reality. And while their constituent elements are not entirely pulled from our everyday lives, they are drawn mostly from just this source. Though, to be sure, the dreams on Elm Street, as close to reality as they are, do feature their own measure of the surreal, presided over as they are by their razor-gloved master of ceremonies, never one to hold back his fantastical arsenal from unsuspecting dreamers.

What A Nightmare on Elm Street doesn’t recreate is the provisionality of the settings, characters, and situations in our dreams. On Elm Street, dreams are basically coherent, the coherence rupturing in one way: Freddy appearing to terrify, disgust, or kill. These dreams are frightening, but they are, in their way, solid.

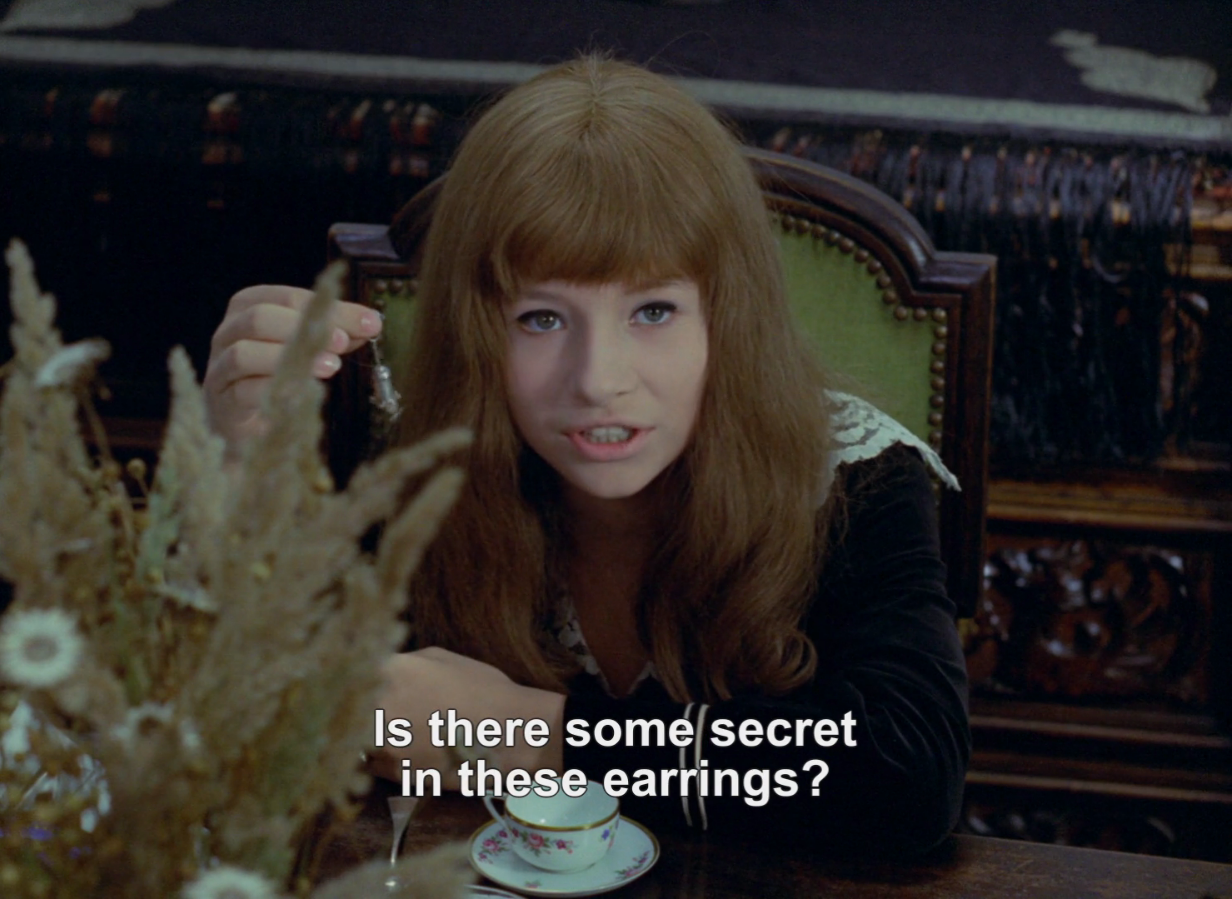

If a commercial slasher requires a certain degree of coherence, we might look to Jaromil Jireš's Czech New Wave classic Valerie and Her Week of Wonders and its gothic horror dream-space to experience cinematic dreaming without this solidity. The specifics of Valerie's dream-journey are never quite clear—or, maybe more accurately, they are clear but not fixed. Consider the character dubbed “the Polecat.” He’s a man in Valerie’s village. But sometimes, for a moment, we see him as a much younger man. He’s also sometimes a monster, an animal (an actual polecat), a dead man, and an undead (or at least formerly dead) man. Or consider Valerie’s nascent romance with the character “Eaglet.” He’s her romantic interest until she’s told that he’s her brother. Later, it’s revealed that this is not in fact the case. And then she’s told again that, actually, he is indeed her brother. Facts in Valerie’s dream world are always subject to revision.

This is a familiar characteristic of dreams. We’ve had those dreams where our coworker is suddenly our brother. Or where we’re in our bedroom, but it’s not really our bedroom, and it’s also maybe a restaurant? Valerie portrays this quality of instability, giving up typical narrative guardrails for a psychic experience that truly proceeds like a dream. Like many of our dreams, Valerie is a film we’d have no trouble describing in terms of what it’s broadly about, but we’d have more difficulty laying out the story in terms of logical, progressive narrative steps.

What we don’t get in Valerie is any direct depiction of the waking world. The film is pure dream from start to finish. (The film depicts a dream-like psychic journey and strongly suggests that Valerie is literally dreaming with lines like "[t]his is only a dream," "I'm asleep," "[i]s this all but a dream?" and a final shot of Valerie sleeping in a bed in an empty clearing). There’s a sense that the major elements of the dream world—incipient womanhood, family history, mistrust of authority figures, sexuality—are the very difficulties Valerie’s negotiating in her real life. Without this sense—some notion that dreams matter—there’s little reason to care about them. Valerie relies on the idea that, in dreams, important symbolic spaces reveal themselves. Valerie imagines a dream space where we connect with the subconscious or other mental depths, journeying into our own psyches. If this pop-Freudian notion is perhaps, in reality, not so simple—dreaming would seem to be as much a process of mental hygiene and processing than of wrestling with our deep complexes, secrets, and fantasies—we do experience dreams as unburdened descents to meaningful mental spaces we don’t inhabit when awake.

Dreams as sites of deep self—as spaces of true, buried motivations for behavior—may not be a particular concern of the first Elm Street film, but it’s an idea central to A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge. It’s a film that makes sleep-walking a central part of the dream experience.

It isn’t simply sleep-walking, really. It’s sleep-control. In Freddy’s Revenge, Freddy tries to take control of high school kid Jesse Walsh’s body to emerge into the real world by way of Jesse’s flesh. In a memorable set piece, Jesse’s gym teacher is murdered by Freddy in the school locker room, but then we see Jesse standing there wearing Freddy’s glove. (There’s a lot we could say about this scene, especially with respect to the subtextual and textual homoeroticism in Freddy’s Revenge. For more on this, check out this piece, or Jesse actor Mark Patton’s documentary Scream, Queen: My Nightmare on Elm Street.) In another scene, we float from Jesse’s basement (Freddy’s domain) up the stairs and through the house, entering Jesse’s little sister’s room and approaching her bed. “Wake up, little girl,” we hear, in Freddy’s voice. But when she wakes, it’s just Jesse, who tells her to go back to sleep. What she doesn’t see is that Jesse is, again, wearing the glove. If Jesse’s dreams are out of control, Freddy’s Revenge tells us, then his body, his whole self, is too. The film weaponizes the notion of dreams as conduits to our deep psyches, to our true desires, motivations, and behaviors. It asks us whether we’re truly in control, really, when this vast, determinative psychic space remains closed off from our waking lives.

Dreams are powerful, also, in their blurry boundaries. Talk of “real world” and “dream world” perhaps misses the fact that the Elm Street franchise is never content to separate dreams neatly and clearly from reality. In the first film, for example, a wide awake Nancy twice gets phone calls from Freddy—and, on one of these occasions, the phone receiver morphs into a mouth, Freddy’s tongue sliding out to lick her. Freddy’s dream world can stab out into the real.

Further blurring the boundaries is the fundamental unanswerability of the crucial, recurring question for characters facing Freddy: whether, in fact, they’re asleep or awake. If you’re starting to nod off and you shake yourself out of it, are you safe or are you now dreaming? Or, if creepy things start to happen, are you currently dreaming? Do you need to wake up? In Freddy’s Revenge, director Jack Sholder plays with these questions when we see Jesse in school, having nodded off in class. We might remember a similar sequence in A Nightmare on Elm Street where Nancy falls asleep in class and then, dreaming, encounters a blood-streaked student wearing Freddy’s glove. Here, a snake slithers over the sleeping Jesse’s shoulder, then around his neck. But it’s not, in fact, a dream. He wakes with a scream. The class laughs. He’s been pranked, and the disapproving science teacher returns the snake to its enclosure.

It’s a scene that illustrates Jesse’s disorientation but also the viewer’s. In A Nightmare on Elm Street, the paradigmatic Freddy kill is Tina’s death at the beginning of the film. She encounters Freddy in her dream, tries to run away but—as these things tend to go—he has no trouble catching up with her. Her boyfriend Rod wakes up next to her and witnesses her death at Freddy’s hands. What he (and we) see is Freddy killing Tina, but with Freddy unseen, the dream attack acting on the real-world body of the sleeping girl. She struggles, razor gloves cut her skin, she’s tossed against the wall and then dragged to the ceiling, and is finally allowed to fall, dead, back to the bed, splattering Rod with blood. We see Freddy's work but not him. It’s a scene that illustrates the general conceptual notion of dreaming (and dream monsters) on Elm Street. The dream world is a distinct realm, and Freddy is stuck there. In the real, waking world we don’t see Freddy—only the horror he inflicts upon dreamers.

But the separation between dream and waking worlds is blurred even in this early introduction to Freddy’s rules and boundaries. When Rod first wakes, before he pulls back the covers to reveal Tina struggling against an invisible attacker, we see, for a moment, Freddy in silhouette beneath the covers.

The waking world/dream world distinction blurs in a different way in the film's iconic bathtub sequence. Nancy begins to nod off in the tub; Freddy’s glove emerges from the water between her legs; her mother knocks on the door, waking her; and Freddy’s arm retracts beneath the surface. For the viewer, Nancy’s nodding off seems less to send her into a distinct dream space but to trigger the emergence of dream terrors into the real. We never exit the real world, continuous space of Nancy in the bath and her mom at the door. Instead, Freddy’s dream world seems to find its way into reality.

At the end of the scene, she again nods off and is pulled into a dark, watery chamber beneath the tub. She fights her way up and out of the tub, but we never see her wake—at least the type of clear waking into the real world that would switch the terror off. She seems to wake when she’s first pulled under. Then she fights, and escapes, and emerges from the bath, encountering her mom (who’s forced her way in at the sound of screaming). We could certainly explain a scene like this with clear dream/reality start and end points: Nancy starts dreaming when she begins to nod off and, somewhere in the struggle out of the bath, wakes. But a viewer doesn’t experiences the sequence with this clarity. For viewers, it’s clear that sleepiness triggers danger, but beyond that the world offers no firm, legible means to distinguish dream from reality. And while character sleepiness guides us a little, we never know, when we first cut into a scene, whether we’re already in a dream. As a viewer, we can never be sure whether we’re seeing reality.

Freddy can really do anything. The nominal safety of the waking world does little good in a film where the perceptual experience offers no clear signposts or rules. And this doesn’t ask too much of an audience because it relies on a kind of meta-rule we all understand: we don't always know when we're dreaming.

In the Elm Street franchise dreams are not the empty calories we sometimes encounter in other films. They are not zero-stakes, contained spaces of easy, unearned scares. In films that open themselves to dreams, they can be, by their very nature, a pervasive source of danger—to the film’s characters and to the world they inhabit.

If dreams can control us and disorient our world, it should be no surprise that dream narratives, thematically, tend to focus on the mind. In Nightmare, defeating Freddy is mental work as much as anything else. Nancy defeats him (to the extent she really does) by turning her back on him, denying his reality, really knowing it’s a dream. In Freddy’s Revenge, Jesse's friend Lisa engages in a similar maneuver, seeing Jesse within Freddy, denying his takeover of Jesse’s body, even kissing Freddy. It’s primarily mental work—a deliberate altering of perception—that allows Jesse, ultimately, to emerge from Freddy’s burning corpse.

Mind and perception are the solution, but they are also the problem. If dream horror narratives offer mental feats as their means of victory, the implication is that the mind, before the third act, was not performing as it should. Stories about dreams can be stories about mental illness.

In the Elm Street franchise, questions of mental illness recur (and feeling “crazy” is an important thread in Freddy’s Revenge), but they’re given special prominence in A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors which finds its Freddy-haunted teens in a mental institution. (For a fascinating personal account of mental illness and Dream Warriors, check out Jessica Scott’s piece in Film Cred.) In the film’s first dream sequence, our protagonist Kristen encounters Freddy in the bathroom mirror, he attacks her, and she wakes, discovered by her Mom with wrists bleeding and a razor in her hand. It’s an incident that precipitates her placement in Westin Hills Psychiatric Hospital. If questioning a protagonist’s sanity is a horror movie staple—did she really see a strange woman in the attic last night?—a disbelieving parent in another film would typically not encounter this kind of stark scene. The horror is in our dreams, in us, and it paints a unique kind of picture. After all, Kristen’s mother is correct: There is something dangerous going on in Kristen’s head. It just happens to be the intrusion of a supernatural villain.

The question for the psychiatrists at Westin Hills is, “What’s going on in there?” Dreams call out for interpretation. We want them to mean something, to have some significance. The dream in Valerie and Her Week of Wonders demands this kind of attention, even if its symbol-rich universe is not completely decipherable. Valerie’s world has its legible symbols (a blood-stained flower, various Christian images) and its more difficult ones (mystically charged objects like earrings and a necklace), but the worldview is clear: the dream world, teeming as it is with allusive imagery, reveals something, or many things, for the dreamer, and for all of us as well.

Dream Warriors also imagines dreams as sites of revelation. The kids at Westin Hills encounter personalized, psychic attacks in their dreams. Will uses a wheelchair but moves without it in his dreams. When he faces Freddy, Freddy confronts him with a spiked, menacing-looking wheelchair. “. . . [W]hen you wake up,” Freddy tells him, “. . . it's back . . . in the saddle . . . again." Taryn, in recovery, encounters a Freddy with narcotic-filled hypodermic needles on his fingers. “Let’s get high,” he says. Her track marks gape hungrily at the approach of the needles. These dreams play on the fears and struggles of the dreamers. These dreams say something about their lives.

They’re also spaces of empowerment. It’s the central innovation about dreaming in the film: dreamers all have a special power they can discover in their dreams. Kristen can pull others into her dreams. Others discover knife skills, super strength, and magic abilities. They’re skills that seem loosely to extend from their personalities. Will, for instance, a Dungeons & Dragons kid, can become “The Wizard Master” in his dreams. It’s a vision in which dreams are revelatory, but they also allow us to encounter places within ourselves that are unavailable in the waking world. In Dream Warriors, dreamers find themselves—or, at least, special, powerful version of themselves—in their dreams. Dreams don’t merely reflect the real world, the real world reaches new dimensions, fully blossoms, in dreams.

There’s a New Age vibe to all of this. There’s a very 1970s, Freud and Jung-shaped worldview animating Valerie And Her Week of Wonders—an insistence that there’s an important personal and mythopoetic meaning to a girl's dreams—and Dream Warriors seems to offer its own kind of mysticism. This is perhaps an unsurprising development in films that take seriously these unstable, fantastic mental worlds. Dreams are a unique site of horror: undermining reality and our perception of it. But dream horror also tends to render dreams as something more. Dreams might explain, control, or motivate our waking lives, and they might emerge as mystical sites in their own right. Not as spaces that merely influence or interact with our conscious experience but spaces of special power or transcendence. Dream horror suggests that if dreams are dangerous, they’re also, potentially, sublime.

Horror writing elsewhere:

Moving to New York after graduating college in the aughts, maybe my main pursuit was watching movies—mostly Film Forum screenings and Kim’s Video purchases. Few films in those early days made as powerful an impression as Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba. Stumbling upon Elena Lazic’s penetrating essay on the film brought its indelible imagery and elemental conflicts flooding back. Seems about time for a rewatch.

Dead of Night has no publication schedule. Sign up to receive new essays about horror cinema in your email inbox.