Rapture | Arrebato

Escaping to cinema, surrendering entirely.

I linked an article about Arrebato in my second newsletter, impulse-bought the Blu-ray, watched it, and have been thinking about it ever since. Finally found the space to write about it. Some spoilers for sure, though I'm careful not to give everything away, especially not about the "vampire" and its secrets.

Content warning: Drug addiction.

Iván Zulueta’s 1979 psych-horror gem Arrebato (“Rapture”) arrived on Blu-Ray and on The Criterion Channel this year with a blurb and a provenance destined to catch the attention of cinephiles and horror-heads. An artifact of bohemian, queer, post-Franco Spain, the Blu-ray cover advertises, “‘An absolute modern classic’ -Pedro Almodóvar” and promises “[a] vampire story without vampires.” Almodóvar isn’t only a fan, it turns out, but provided a voice dub for the character Gloria. And Zulueta was, for Almodóvar, an important friend who designed several beautiful posters for his films. That the answer to the riddle of Arrebato’s vampire-lessness turns out to be that cinema itself is the vampire only adds to the film’s allure—at least for those of us with a taste for metacinema. And if all of the above conjures a heady brew, it should be said that—while these are all important elements of Arrebato—it still does not quite capture what’s going on in the film.

Arrebato is both “metacinema” in the strict sense—a film that calls attention to itself as a film—and a film about films in a more general sense, asking questions about film, filmmaking, and making art. Criticism of self-referential works of art can be sometimes content to simply note the self-referentiality—to spot the meta-moment (and, to be fair, they can at times be little more than winks at the audience)—but for Arrebato this will not do. Arrebato does several distinct things with film and filmmaking. It's this deep, restless engagement with cinema that gives Arrebato much of its potency.

Arrebato operates on two timelines. In one, film director and heroin addict Jose returns from the editing room to his Madrid apartment to find a package from Pedro—an acquaintance/lover—and the sleeping figure of his (also strung out, ex-?) girlfriend Ana. The package contains a reel of super 8 film and a cassette of recorded audio. As Jose listens to the audio and watches the film, we’re shown flashbacks of his relationship with Pedro, beginning with his first introduction to the film-obsessed cousin of his friend Marta. We learn about their past, Jose’s current heroin-clouded life, and Pedro’s unusual filmic pursuits, which eventually veer into the uncanny. The two threads will, of course, intersect again, as the conclusion of the super 8 footage and audio tape send Jose off on his own, dark mission.

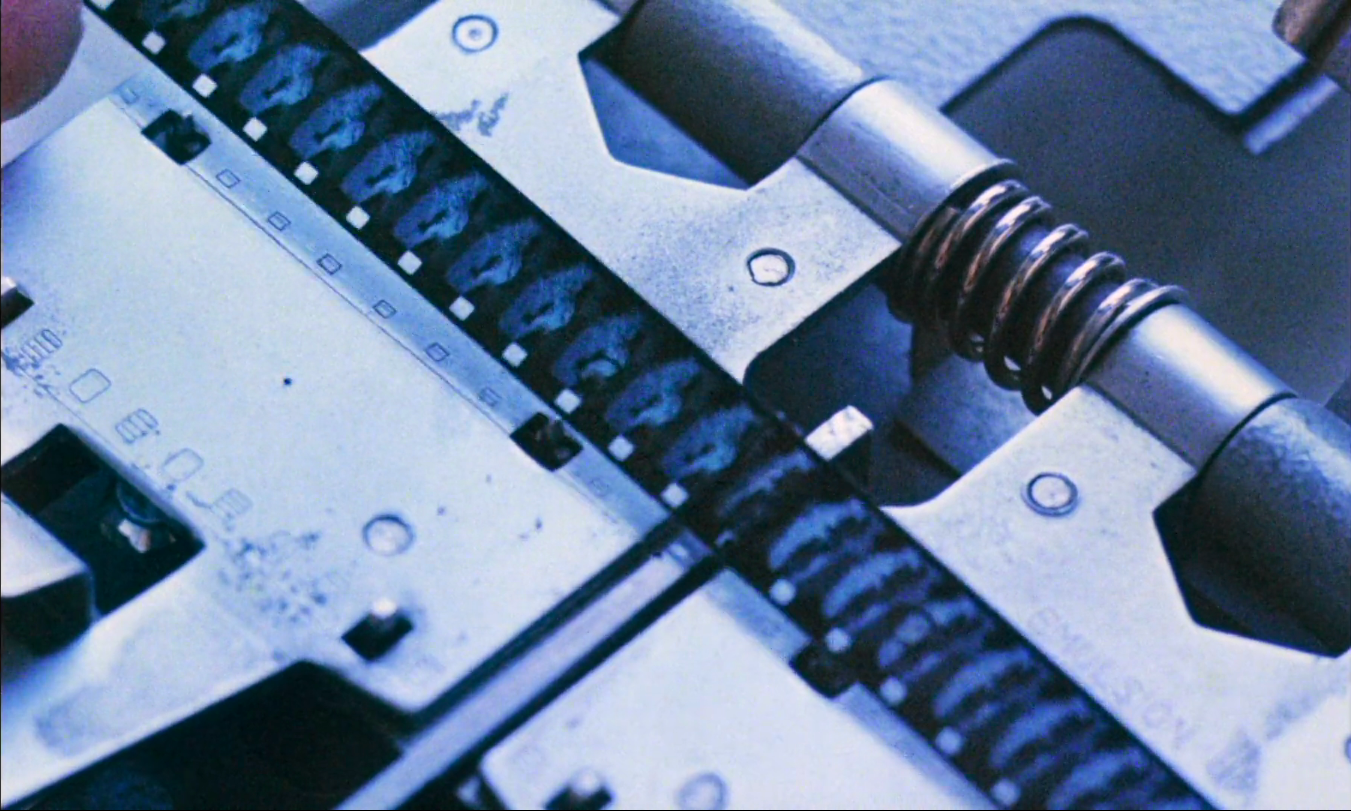

Arrebato's pre-title opening finds Pedro assembling the super 8 reel and recording the final bit of audio, preparing the package for Jose. The film is not only about the content of these materials—they’ll draw Jose into Pedro’s world, and he’ll find something supernatural within them—it is, to a great degree, about their material creation. Our story occasions the filming of what we see projected in super 8. And the relationship between Jose and Pedro generates the audio recording that provides the film's voice-over. The super 8 film does not illustrate anything—it is not the emotionally charged home video (usually prominently featuring a deceased spouse) so familiar from other films—it is the center of the film, just as it is, also, the film itself. Arrebato is about these materials and, at the same time, made up of them—its frames and audio tracks taken over as we watch super 8 reels, some in flashback, some in present tense, and we hear the audio. This is a film that is the thing that it’s about.

It’s also a film about film directors, so it’s maybe no surprise if we sense the hand of a director within the frame, though here it will be the amateur—Pedro—doing the directing. Pedro’s designs loom over the film. From the first meeting of Jose and Pedro (“You passed the first test easily,” Pedro says in voice-over), Pedro seems to have plans and expectations for Jose—even if his precise aims are often hidden or vague. And it’s his creative journey, documented and delivered to Jose, that ultimately sends Jose on a lonely chase after filmic vampires.

Though Jose is not a mere pawn in Pedro’s world. He’s a kind of muse, critic, and collaborator. Pedro has a need to show him his (at first boring, amateurish) movies and asks him quasi-mystical questions about filmmaking that Jose doesn’t (at least initially) understand. For Pedro, their first meeting is a turning point. He seems to have been at a creative dead end. Jose came at a “crucial time.” And again, later, stuck in another creative cul-de-sac, Pedro receives an interval timer in the mail from Jose, and it revives his filmmaking. The two are, throughout, collaborating on Pedro’s movies and on the movie we ourselves are watching.

Even so, the shape here is not quite that of the Künstlerroman (“Künstlercinema?”). Pedro may be maturing as a filmmaker (after he receives the interval timer, there’s a marked advance in the quality of his work), but he can’t be said to come into his own as an artist. Instead, he finds, in his obsessive devotion to his art, a supernatural force lurking in cinema itself. As he finds it, the distinction between author and subject blur: Pedro moves in front of the camera, and the camera begins to run on its own, its click-click and flashing red light calling to him, prompting him to come into frame. We even witness the camera pan on its tripod without human aid, animated by some force found in cinema. He is neither master of his art nor in some easy, balanced relationship with it. Cinema has a hold of him.

Cinema's role progresses to conduit of the supernatural, but it's already found its place as a site of expressionistic revelation—of emotion, of interiority, of the surreal flourish. There’s the early scene where Jose’s watching TV with Marta, her Aunt Carmen, and Pedro, drones kick in, and the film on TV begins playing at an ultrafast speed while Jose's fixated on the screen. It all conveys a rapt, out-of-time experience with the movie. Afterward, Aunt Carmen notes that he hasn’t touched his coffee. He’s been entirely absorbed. Later, flashes of grainy film footage of cheery and erotic imagery of women knit together a present-tense dour conversation between Jose and Ana (their relationship destroyed by their mutual addiction to heroin) and a flashback to the two of them in bed together in happier times. The footage connects Jose’s dismal present with his escape into memory. And there’s the moment when, following the vampire to Pedro’s apartment, Jose looks out window, and we cut to moody time-lapse footage of the sky. Cinema provides, again, the emotional register.

Cinema in Arrebato cannot really be discussed on its own. It winds its way around the film’s other big subjects. Cinema and addiction never stop interacting, and the film looks plainly at heroin’s ravages, but it never uses cinema, or the supernatural in cinema, as simply an addiction metaphor—even if it is undoubtedly that. Cinema and heroin may both be vampires in this story, but like many of our vampires, they are not just monsters, but creatures with their own allure.

There’s a moment where Pedro describes his next couple moves once the supernatural in cinema has taken hold: “two times, two dreams, two doses, two raptures.” It’s a line that suggests the intermingling of cinema and narcotics —and of desire and sexuality, a third essential element. The film’s called “Arrebato”—rapture—and the possibility of rapture arises naturally in the context of desire, but also at the sharp end of the needle, and in Pedro’s unwaveringly mystical cinematic experiments. Cinema here overlaps always with addiction and with desire. There’s no disentangling them.

When we first see Jose, he’s in the editing room arguing with his editor about whether to use a specific shot in the vampire film they’re making—a shot run in reverse in which the vampire looks directly at the camera. The editor’s concerned with standard, commercial cinematic values, but Jose wants something else. Jose demands that they use this fourth wall-breaking shot, saying, “It’s the only interesting thing in the whole picture.” The notion here—that amid the hours of raw footage produced in making a feature, there might be just one interesting shot—turns out to gesture at an animating idea in Arrebato, especially in Pedro’s cinematic undertaking. Pedro is obsessed with cinema, but he doesn’t want to be a commercial director. He aims at something fleeting, difficult, hidden. It’s something to do with time and timing, as Pedro’s cryptic remarks about “pauses” and “rhythm” make clear. Before he leaves home to travel with his camera, he says, “I’ll discover thousands of hidden rhythms. The mirror shall open its doors and we’ll see the . . . the . . . the other.” He of course does find something “other” hidden in cinema—something rapturous, something beyond rational explanation.

The constant desire for something hidden and ephemeral has its analog in addiction’s cycle of want, rapture, and degradation. Jose’s present-tense life is one of simmering dissatisfaction, broken up only by drug use and by memory. And Jose’s desire for other people is its own kind of restless search. Marta, Ana, Pedro—all lovers, but none an endpoint. Or, if Pedro becomes an endpoint, it’s at a place beyond romance or sexuality.

What is the cinematic thing Pedro (and later Jose) are pursuing? What is this “other,” this rapturous thing? We can say for certain that it’s something outside the ordinary experience of our lives, or of time. Pedro’s concerned with the power of objects from childhood to fully absorb a person. There’s a scene in which Pedro sits Ana—floating on a heroin high—in front of a Betty Boop doll he’s somehow procured that seems, to her, to be the favorite doll she had as a child. The heroin and the doll fully enthrall her. She’s captivated, so much so that Jose and Pedro sleep together, in the same room, while she gazes at the doll. It’s a scene that points to the mysterious things its characters are chasing through cinema. As with the depiction of Jose captivated by the TV, Ana is in the thrall of an image—an image in which she loses herself entirely.

The doll’s power corresponds to that of other objects from childhood, objects about which Pedro comes as close as he ever does to explaining his notion of the “pause.” Pedro asks Jose what his favorite trading cards were as a kid. He tells him they were the King Solomon’s Mines cards, and, sure enough, Pedro brings out a set to show him. Pedro describes, as Jose examines the cards, the thing about them that captures his interest:

Tell me, how long could you spend looking at this trading card? And this one? Remember? And this border? And this other one? Years . . . Centuries . . . An entire morning . . . Impossible to know. Pure escapism. Ecstasy. Suspended in pure pause. Enraptured.

The thing Pedro’s looking for in cinema—that hidden thing, the thing that leads him to his vampire—is something akin to losing oneself in these talismanic objects: something outside of time, a rapturous escape. And again, the correspondence with heroin or sex jumps out at us.

If Arrebato’s a film about art, desire, and drugs, it might sound like a document of bohemian Madrid. The film does emerge from this setting and, at times, depicts it. But it’s not a film that quite embraces the counterculture—or any culture at all. There’s a distinct antisocial aspect to the path taken by Jose and by Pedro. Jose—in the present—has lost almost all interest in Ana. And he appears to be mostly a passenger in the production of his own film. Pedro, pushing ahead in his strange relationship with cinema, is content when isolated. He describes social entanglements as being “trapped by so much bullshit.” We see footage of Pedro at a party, surrounded by people, and he looks a wreck, not up for it in the slightest. Holed up in his Madrid apartment with his camera, he gets a knock at the door. It’s his friend Gloria. He’s reluctant to let her in and, when he does, he describes it as a “mistake that almost cost [him] [his] life.” A strange, erotic, and violent night out follows: punkish music blaring (Negativo, a Stooges-sounding group featuring Zulueta’s brother Borja) as the duo prowls the street, scaring normies away, having a three-way sexual encounter in an elevator, and ultimately sending their new friend running—bloody and naked—out of the building. It’s not entirely clear what happens before that final moment (the camera never follows the three of them up the stairs that the guy runs down), but Pedro describes the whole thing as “drifting away from destiny.” Whether the world out there is scary—or he’s too scary for it—it’s clear that what he wants, ultimately, has nothing to do with other people.

It’s a bit grim and so is Arrebato. The film may not settle for simple metaphors or cautionary tales—a tale of cinema/addiction as merely a descent—but it is that too. There’s no reason why a pursuit of mystical, out-of-time escape should produce a vampire—but this is precisely what it does. Pedro, and later Jose, look terrible, strung out, as they visit the camera shop to develop their film. Marta tells Pedro, of his final cinematic obsession, “Pedro, this may be dangerous! Have you looked at yourself lately?” Jose’s relationship with Ana circles the drain throughout. His consistently cruel treatment of her culminates in excruciating cross-cutting between Pedro’s story and Jose watching his reel and listening to the audio cassette as Ana aggressively tries to seduce him. He finally pushes her off angrily, saying, “You know that this fucking horse kills our sex life!” It’s a collision of cinema, desire, and addiction—but not a harmonious one.

Or, at least, in these moments, it doesn’t feel like one. Arrebato is as much a vision as a narrative. A film about its own creation, in which its principal director’s final step is to place himself in front of the camera—cinema’s subject, not its author—Arrebato acts out a surrender to cinema. Cinema here is the site of the supernatural, a conduit of emotion and interiority, and a way to escape our lives. There’s magic here—in cinema, and in narcotics, and in desire. Arrebato insists on the magic of cinema but in such a way that it would never be mistaken for a “love letter.” What’s magic isn’t always good, or easy, or containable. A rapture may be a welcome escape, but an escape, also, into the dark.

Horror Writing Elsewhere

As a lover of horror and of the desert, I was always destined to be a fan of Stephanie Rothman’s The Velvet Vampire. And this "Classics Corner" column by Sean Burns outlines what's great—and, also, what's not so great—about the cult classic. A good October watch, especially for those of us in Southern California.

It's available on several streaming services, including for free (with ads) on Tubi.

Dead of Night has no publication schedule. Sign up to receive new essays about horror cinema in your email inbox.