Public Dread and Gakuryū Ishii’s Angel Dust

I stumbled across Angel Dust, a film I'd never heard of, only a couple of weeks ago while browsing Letterboxd. It seemed—from the reviews focused on its visual style, its depiction of Tokyo, its dreamlike feel—like something I should see, and I was happy to find it on YouTube. And yeah, it's a wild ride that might have coaxed ten different essays out of me. Here's one of them.

Medium-level spoilers ahead.

ALSO, I've added a new feature–"Watched/Read"–where I recommend something (or more than one thing) exciting in horror that I've watched or read or experienced since the last newsletter.

Content warning: serial murder, covid, terrorism, military violence.

Serial killings, if they are known, bring with them an atmosphere, a sense of communal fear. On-screen, this phenomenon is not an unfamiliar element of the serial killer film, though generally without the potency it has in Gakuryū Ishii’s moody mind-melt Angel Dust (1994). An ambitious, bizarre, quite disturbing serial killer movie, Angel Dust becomes, by its end, a film about brainwashing and highly personal agendas—but it gets there by enveloping Tokyo in a heavy atmosphere of public dread.

We’re among commuters on a train in Tokyo. It’s approaching six p.m., and the home-bound office workers crowd the cars. Everyone inhabits their own little world—reading the paper, listening to music, staring into space. What’s happened to a young woman standing quietly in the crowd goes unnoticed until she falls, landing at the feet of the commuters around her, dead on the floor of the train.

This is the recurring murder sequence in Angel Dust. And, at least at first, it happens this way weekly, at the same time. A young woman is killed on the Yamanote train line, jabbed with a toxin-laden syringe, at six p.m. every Monday. It’s a more precise, predictable pattern than we’re used to. There’s no sicko furtively waiting for an opportunity—there’s a killer’s inexorable design unfolding freely, dependably, in the city.

The crystal clarity of the pattern has a theatricality to it. It announces the next death, and where and how it’s coming. Ishii let’s us experience, with the public, the approach of the appointed time. Text on screen tells us it’s Monday, an angle on a clock or watch shows that it’s almost six. Someone will die—any second now. It’s a collective experience of vulnerability.

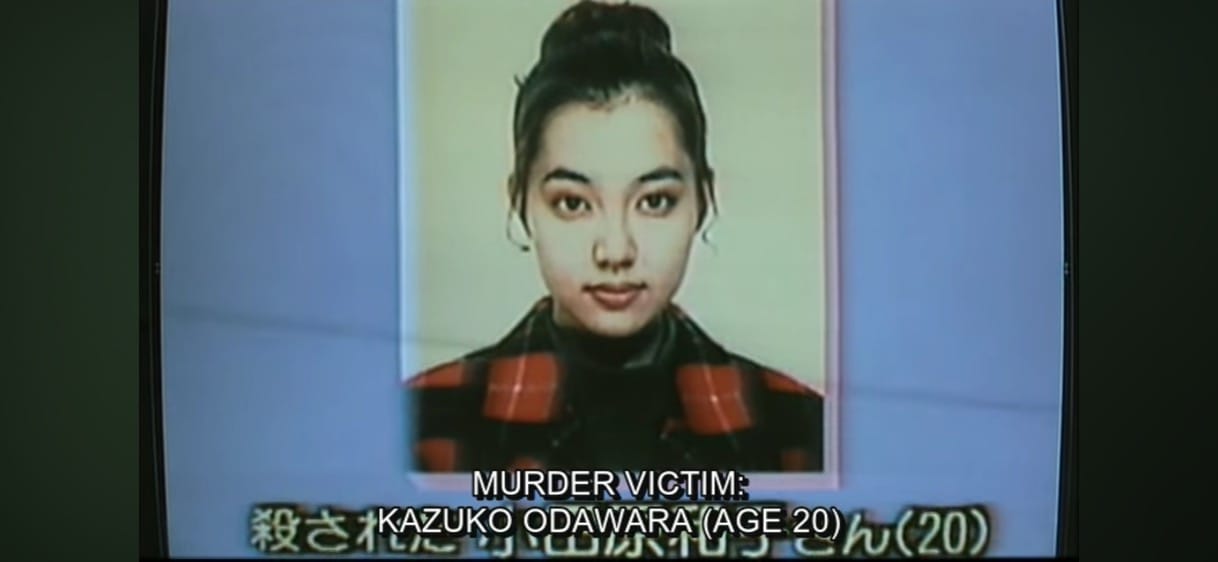

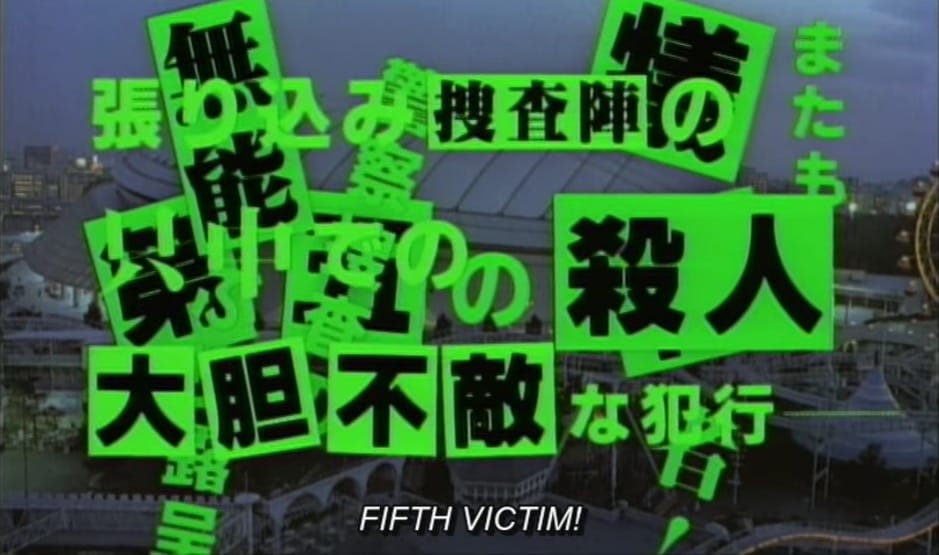

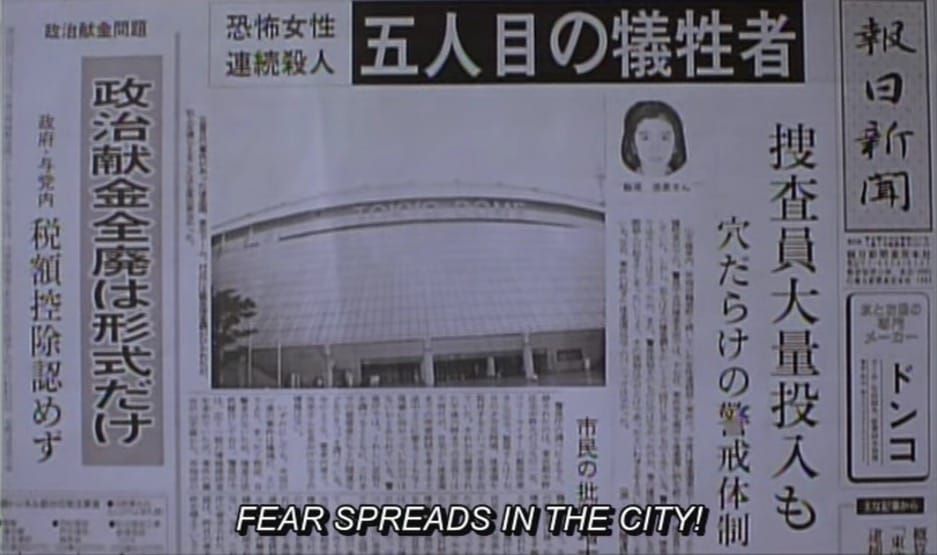

The experience is heightened as well—and more conventionally—by a returning attention to local media. Headlines are splashed across the screen. We see clips of TV news. We see newspapers. The city feels it, and we— fists clenched as six o’clock approaches on Monday evening, or gazing anxiously ahead on Tuesday morning—follow along with the public.

Angel Dust let’s its patterned killings subject its public to a generalized sense of dread—the dread of a city trapped in a killer’s routine—but it also targets Tokyo's public by imparting a sense of danger to its crucial, connective public spaces. Ishii’s treatment of these murder set pieces in and around public transit relies, some, on genre-familiar features—propulsive music, a windy whistling associated with the killings, police weaving through the crowd—but the power of these settings mostly derives from the naturalism of their staging. There’s a focus on the size of the crowds, their churn, their multi-directionality. In a different context, it might be a mundane depiction of commuters headed home. It’s our knowledge of the coming murder that shifts what’s mundane into something frightening. What’s just a crowd now teems with risk—a killer and a victim are in it somewhere, impossible to pick out.

In horror, our level of fear can be tied to location. Distinctions of private/public and alone/accompanied tend to shape our sense of danger. This is true in life too—we meet a stranger in public, not at our home. In Angel Dust, in these public transit set pieces, the charge of these distinctions is reversed. We are unsafe in public, unsafe in a crowd. It’s democratic, communal, well-lit space that poses a danger. We’d be better off in a cabin in the woods.

By the end of Angel Dust, we do meet the killer, but during these murders in public, the killer is never seen (The sole exception being a more generic killing at a laundromat in which we briefly see the killer’s arm). The method of killing—the jab of a syringe, which we also never see in these scenes—is also rather restrained. Our eyes may strain among the crowd for some sign, some meaningful glimpse, but futilely. In these train line murders, the killer is disembodied, almost abstract. Someone in the crowd will die, silently—the cause a ghost in the throng. The source of terror feels less like a person, more like a curse.

Coming through a worldwide pandemic, the notion of an invisible threat in the crowd is a familiar one. Other real-world scenarios come to mind as well—terrorism, military strike, even the sudden jostle or trip onto train tracks. In Angel Dust, we find a heightened version of everyday public dread—there are recurring dangers that we cannot avoid, only anticipate. And we’re forced to see the danger in the central, connective public spaces of our cities. Our killer is less a wild deviant disrupting normalcy, more a reminder of the collective dread that haunts us every day.

Horror Writing Elsewhere

I loved Theo Spielberg's exploration in The Los Angeles Review of Books of Fatima Al Qadiri’s score for Atlantics—a horror-adjacent standout in 2019. Music can signal genre, but it can also complicate or blur it, or shepherd the visual from one genre to another.

Watched/Read

I recently rewatched The Spiral Staircase at the New Beverly Cinema and it was more of a horror movie than I remembered. We think of Robert Siodmak's beautiful, deep-focus mis-en-scene in thrillers and noir, but it's potent here, in a film which is quite scary, a proto-slasher even. An eye watching a woman from a closet, a killer's POV, black gloves—giallo vibes in 1946, in the States.

Dead of Night has no publication schedule. Sign up to receive new essays about horror cinema in your email inbox.